As technology and culture progressed throughout the 19th century, the Navy adapted its strategy and training to be an invaluable asset during World War I. Most notably, the Marines continued to make a name for themselves over the years as some of the toughest, roughest and courageous troops on either side of the Atlantic. Our previous post on the man who inspired part of the Marine Corps hymn when he stormed through artillery fire to plant the first American flag in old world soil is indicative of the fighting spirit that carried on throughout the Marines’ military tradition.

It was during World War I that the Marines made a name for themselves as the “Devil Dogs.” By the middle of 1918, American forces had been deployed to France for over a year. During this time, however, American forces played primarily a supporting role for allied troops, not yet proving themselves as an independent and worthy force in their own right. Then, the Battle of Belleau Wood began.

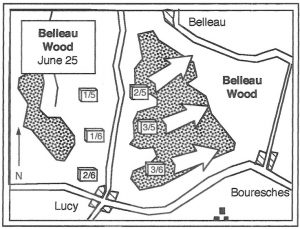

While American Expeditionary Force (AEF) commander John Pershing pushed north to capture the city of Cantigny, German troops launched an unexpected offensive in the south. German forces easily compromised allied defenses and pushed forward to the Marne river, hoping to establish their forces within striking distance of Paris. The 2nd and 3rd AEF divisions rushed to the Marne region to repel the German advancement against Paris. James Harbord, an old chief of staff for Commander Pershing, led two brigades of Marines and soldiers from the 2nd to the village of Bouresches and nearby Belleau Wood.

What would soon ensue would be the bloodiest battle in the Marine’s history to date. Five German Divisions advanced against Harbord’s single, subdivided 2nd Division. Upon arrival, Marines were met with fleeing allied soldiers, urging them to retreat. In a sardonic response that characterized these Marines, Captain Williams famously responded, “Retreat? Hell, we just got here.” Refusing to give ground, Harbord and his men forced the Germans to bunker down in Belleau Wood and planned for their counterattack.

While one regiment of Marines took and defended the nearby village of Bouresches, engaging in hand to hand combat as they rooted out German soldiers, the remaining force focused on taking Belleau Wood and repelling the German advancement. However, the introduction of the machine gun proved more deadly than the Marines anticipated. Advancing on Belleau Wood on June 6, 1918, entire regiments of Marines were torn to shreds. They pushed on amidst the machine gun fire culling the fields, encouraging each other with, “C’mon you sons of bitches, do you want to live forever?” By day’s end, 228 Marines were killed in action and 859 more were wounded–more casualties than in all of Marine history at that point.

Day after day this assault continued. For three weeks the Marines fought for every inch, unbreakable in spirit as they advanced into Belleau Wood. Artillery and gun fire began to lessen the deeper the Marines advanced into the woods, and the modern conventions of war fighting gave way to desperate hand-to-hand encounters. Navigating through clouds of mustard gas, the Marines proceeded to ambush the last of the entrenched Germans with bayonets and extremely lethal “toadstickers”–which are somewhat akin to brass knuckles, except they are attached to a large, triangular blade. It was during this advancement that the German soldiers began referring to these men as Teufelshunde, i.e. “Devil Dogs,” emerging from smoke.

June 26 marked the complete victory of the Marines over Belleau Wood, and with it the cessation of German advancement upon Paris. Upon hearing news of this victory, Robert Lee Bullard, commander of the U.S. First Division, stated: “The Marines didn’t win the war here. But they saved the Allies from defeat. Had they arrived a few hours later [it] would have been the beginning of the end. France could not have stood the loss of Paris.”