On August 15th, 2021, I walked into the Rayburn House Office Building for my first day of work – my first job after a decade in the US Army. Kabul, Afghanistan had fallen to the Taliban in the early hours of Eastern time. It was then a certainty that the oppressive, radical group that had taken so many American lives, would once again, rule the country.

I never deployed to Afghanistan. I spent all my deployments on the Arabian Peninsula and Syria. For that reason, I believe I was able to look at the rapidly expanding problem objectively. Our district office received a call about 23 school-aged American citizens that were stuck in Afghanistan, unable to leave the country. At that point, we had more questions than action items. Why were they there? How long had they been there? Didn’t they know the country they were in was being overtaken by Taliban? Summer vacation – they had been there visiting family over summer vacation, and one hell of a way to spend it.

“Okay,” I thought, “what are we supposed to do now?” I was so new I didn’t even know where the bathroom was and the senior policy advisor said, “you were in the military, see what you can do about Afghanistan.” The senior foreign affairs staffer, a field representative from the district office (a veteran himself), and I started making phone calls, starting signal chats, joining Slack channels, and texting old interpreters over WhatsApp across the Middle East. We stumbled into an official ‘cell’ that could extract Americans. We developed a quick standard operating procedure of what was needed – location, name, passport number, etc. – and started to send it, one after another. We coordinated information while the ‘cell’ deployed air assets where a group of ninjas would escort Americans out of danger. Our first success was our largest. The 23 school kids and their parents were exfiltrated and home quickly. Media picked up on the success and calls flooded into our office. I took enough of them to come to a frightening conclusion – ‘if our district has this many Americans stuck in Afghanistan, other offices must have the same calls.’ 435 House offices. Odds are that there are thousands of Americans stuck without US assistance. We did some informal polling across offices and vindicated our theory. At best, there were a couple thousand blue passport-holding Americans, just as many green card holders, and an untold amount of Special Immigrant Visa applicants (a program developed to provide a pathway to US citizenship for Afghans who have helped the war effort over two decades). I called the Pentagon. I knew from the Colonel’s tone of voice and his talking points that they were at least theorizing the same numbers with an equal feeling of helpless horror.

Videos of the Hamad Karzai International Airport (HKIA) were now on infinite reel on the news. Stories of deaths from stampede, dehydration, and stray Taliban rounds started to fill our Signal chats and Slack channels. A mother, after being denied entrance to HKIA for inadequate documents, threw her newborn baby into the sewage canal next to Abbey Gate. US Service Members attempted to revive the newborn to no avail. Self-preservation? A swift end to an undoubtedly nasty and brutish life under Taliban rule? I cannot begin to know the reasons why that mother would commit such an act, but that is a mystery that will haunt me for the rest of my life.

The airlift was underway. The DOD did their job: execute policy. Watching the amount of C-17s come and go was a logistical masterpiece. The symphony of Air Force Operations Centers from Hawaii to Washington to Germany to Kabul seemed to be in perfect harmony. The only solace I took from this disaster was the reassurance that American airlift capability was intact – it was becoming vividly clear to me that was the only thing that was going to work right.

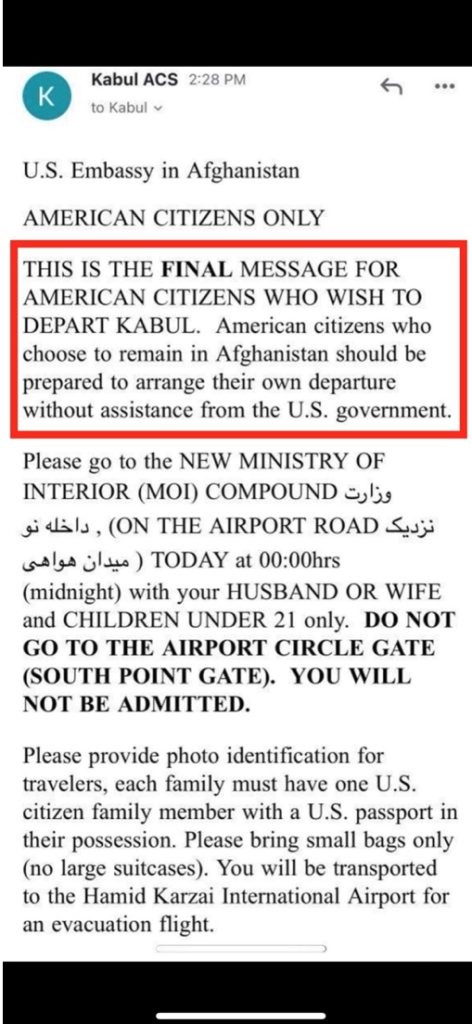

Our office had a constant barrage of email messages to the State Department about flights, manifests and general frustration about the pace of issued visas. I dealt with the State Department enough during my time in the military to know that they shouldn’t be in charge of the largest airlift in history. We began to receive an automated email that circulated among the groups. I received my own the morning of August 24th:

“This is the final message for American citizens who wish to depart Kabul. American citizens who choose to remain in Afghanistan should be prepared to arrange their own departure without assistance from the U.S. government.” Without the assistance of the US Government? The State Department has a legal obligation to assist blue-passport holders under USC 22 Chapter 23 section 1731: Protection to naturalized citizens abroad. Where was that protection then? Where is that protection now? Over the past two years, I’ve had plenty of tense conversations with State Department representatives – we almost always arrive at the same conundrum where State Department Representatives ultimately tell me they have no physical presence in Afghanistan and, therefore, cannot do anything to assist. This infuriated me – every single time.

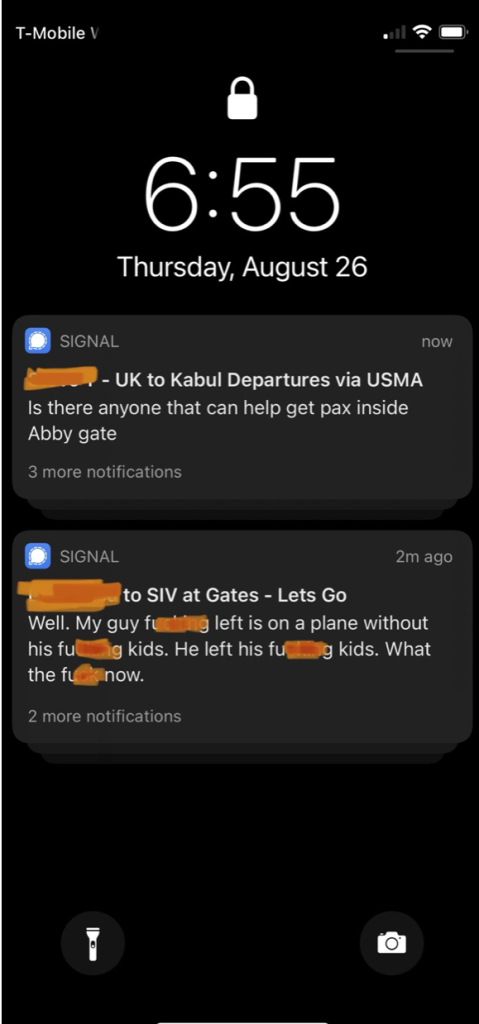

You didn’t have to see the news to know that HKIA was in complete disarray. I’d wake up to 800 plus messages of desperate pleas to get someone, a family, children, onto the airport and into a C-17. On August 26th, I scrolled through my messages then set my phone down to make more coffee. I picked up my phone to this:

I read the message about an Afghan leaving his wife and children. I laughed. Then I cried. I got ahold of myself and noticed a familiar feeling – like I was on deployment, always on, but I was standing in my kitchen in northern Virginia with my own wife and children sleeping 30 feet away. I hated it.

I remember being on the phone with a colleague in the car when I started to get notifications about Abbey Gate. At first, they were heightened alerts, then early reports of an explosion. We all knew HKIA was a physical security nightmare, and the fact that the United States’ clock was ticking on permanent withdrawal only conflated the chaos. The good Lord and I have a unique relationship, but I remember saying a prayer because I knew there were US soldiers at that gate. It wasn’t until later that day John Kirby confirmed US Service Members were among the dead. I was enraged. I choked back tears at my desk. I’m pretty sure others noticed, but didn’t say anything to the tough Army guy – I was melting on the inside. Every day this debacle continued the more disillusioned I was becoming. This was the quick and ugly education of a soldier in Congress.

Once the next-of-kin was notified, the names of the fallen were released. SSG Ryan Knauss had been in the same Regiment as I was. He was younger, but I remember running into him during training and seeing his name at various events. He was a good dude (one of the highest compliments in the military), destined for great things in the Special Operations community. Ryan, and the 12 other Service Members who died that day paid for the policy failure. They will not be forgotten. Lest we forget the 170 plus Afghans who died just waiting for a ride. No one asked if any of them were clutching a blue passport or green card along with their belongings. Odds are, there were certainly Afghan Americans within that crowd.

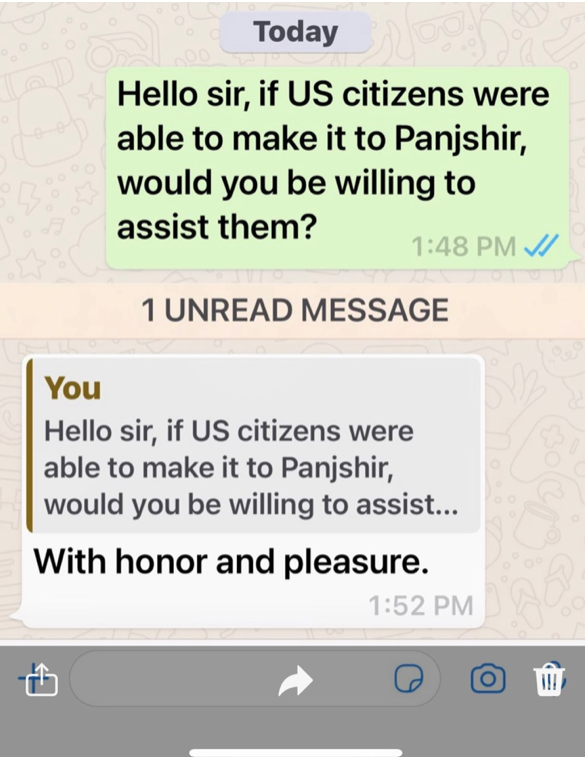

Later that day, I took a shot in the dark and through an interlocutor, contacted the Afghan Vice President, Amrullah Saleh. Since Ashraf Ghani bailed with a bag of cash, the Afghan constitution stated that Amrullah Saleh was the rightful President of Afghanistan. There were reports that President Saleh had made it to the Panjshir Valley with The Lion of Panjshir, Ahmad Massoud – son of the slain revolutionary, Ahmad Shah Masoud. I asked a simple question: if American citizens could make it to Panjshir Valley, would Saleh and Masoud keep them safe until the US could come get them? Saleh’s answer, was just as simple: “with honor and pleasure.” The humility was beyond me. I socialized the option of sending small groups of Americans to Panjshir for temporary safety. This, of course, gave Masoud and Saleh great leverage as well, but no one else was floating any better ideas at the time.

The following days showed that Panshjir Valley was simply not a viable option. The resistance that was strong in heart and weak in numbers began to crumble and dissipate. That was the last hope we had for an Afghanistan that could stand on its own.

After the bombing, there was no easy way to get Americans onto HKIA. Our networks vanished as the DOD (more likely DOS) had locked down Kabul – no one outside the wire. From August 26th to the final day on the 31st, there were no wins. 20+ hours a day of emails, phone calls, signal chats, WhatsApp, Slack and Discord – searching for any weak signal of opportunity. Those six days were a complete blur, but I don’t recall getting a single person onto a flight out that wasn’t already on the tarmac. It was depressing. The phone would ring and someone would have a tip. Adrenaline would flow and I’d flip through my mental rolodex of people to call or message who had a seat on a flight or knew someone to bankroll a private plane or had landing rights in some obscure country. No one showered or ate. My wife and kids had left on a pre-planned trip back home to see my in-laws. Good thing they did. I didn’t want anyone to see me in the state I was in – even my wife. It felt like a deployment, only worse, because I was alone on my living room floor switching between laptops and phones. I didn’t have a battle buddy to share my misery with in person, only over the phone between frantic ideas.

August 31st came early. Gates were welded shut sometime during whatever semblance of sleep I was getting between the 30th and the 31st. That was essentially the end of our panicked phase. Now came a deliberate, long game. While I was deeply disillusioned, enraged, disappointed, confused, and despondent, I felt a wave of relief come over me. It was the same relief I got when I landed in the United States after a deployment. I picked up hardened scrambled eggs off the kitchen floor my one-year-old son had dropped off his highchair 6 days before and went to the grocery store. I had a long conversation with a representative from Task Force Pineapple about the past couple weeks. There was agreement that this was only the beginning. There would be much more to do in the coming weeks and months. That was a gross understatement.

I had no idea the types of hurdles and mountains of excrement that had been heaped onto this debacle. Some of the atrocities would come out before the years’ end, but we are still learning of this Administration’s gigantic ineptitude in handling the withdrawal. Secretary Mayorkas went in front of a Senate Homeland Security and Government Affairs Committee and told the world that only 3% of the 60,000 Afghans that came to the United States were eligible for Special Immigrant Visas. Virtually every military leader from the Secretary Austin to General Milley and then CENTCOM Commander, General Mckenzie, testified that they had advised President Biden on leaving a small contingency of troops in Afghanistan to support the Afghan government and continue to train Afghan forces engaged in counter terrorism missions. President Biden didn’t mention the Afghanistan withdrawal once in his State of the Union address. The State Department has told Congress that 800 American Citizens have been evacuated since August 31st, tens of thousands of Long-Term Permanent Residents (LPR, or green card holders), and I’ve heard Special Immigrant Visas are backlogged to the tune of between 70,000 and 250,000 Afghans still waiting for their case numbers to be processed. Meanwhile, the Afghan National Army and Special Operators, that US Service Members trained and equipped, have no pathway to the United States. This whole withdrawal was backward from the start and only perpetuates today.

Looking back on the last two years, it’s easy to feel betrayed. As a soldier, I volunteered for something bigger than myself – sure, I wanted to jump out of airplanes and blow stuff up, too. But that blue passport meant something. It was ticket out of a bad situation. That’s no longer the case for me and I know there are many more out there who feel the same way. We have to believe that our government will be our ride out. We have to buy into that social contract of mutual trust. Our government must be able to function enough to agree on doing everything possible to move American citizens out of harm’s way. I was surprised that getting Americans out of Afghanistan, while it fell apart, was not bipartisan. There were those who simply would not speak against the Commander-in-Chief and literally hung up the phone when constituents called for help out of Afghanistan. I took a call from an Afghan in a neighboring congressional district who told me their representative told him that “we don’t do Afghanistan,” and hung up on him.

President Biden could have made Afghanistan a priority – one with follow-through. Instead, it is one tainted in dissonance. There are still hundreds of Americans in Afghanistan, as those patriotic hold-outs come to the realization that the Taliban is not ruling with a new groove – they are the same repressive, radical idealogues that will change just enough for the world stage to notice, then go right back to 7th Century rules. The SIV backlog continues, and global conflicts only prolong the inevitable – sometime soon the State Department will change the rules and tens of thousands of Afghans will become ‘ineligible’ for a pathway to the United States – just as they are in the Emirati Humanitarian City.

Afghanistan may become, or even feel like now, a distant memory. It is not – not for the Gold Star families and those who lost brothers and sisters. We have not forgotten what wrong looks like. The innumerable veterans who watched in disgust and those who acted to assist a country where so many of them bled will not forget either. I was never a good Non-Commissioned Officer. I didn’t know any cadences, couldn’t stay in step, and I had an uncontrollable smile whenever someone yelled at me (this got me in lot of trouble). There was one thing that I took from my early indoctrination in the conventional military – the definition of responsibility: being accountable for the things I do and [more importantly] the things I do not do. The silence of what was, and is not, done in the name of Afghanistan by this Administration is deafening.