From the first days of U.S. involvement in Afghanistan, through the final weeks of our chaotic withdrawal, Afghan forces have enabled the success of U.S. special operations forces (SOF) and intelligence personnel operating in the country.

When the Taliban took control of Afghanistan in August 2021, members of the SOF community banded together to form nonprofit organizations or white-knuckled solo efforts to support their Afghan counterparts. Continuing that effort over four and a half years has often been grueling. SOF allies left behind during the withdrawal waiting to be processed through U.S. programming have lived as refugees in expensive third countries or gone into hiding in their homeland to evade the Taliban’s ongoing reprisal campaign. Afghans transitioning to a new life in the U.S. have had their own unique challenges, including separation from family and a lack of permanent identity while living under temporary protections like humanitarian parole.

After a heinous shooting attack conducted by an Afghan national in Washington, D.C. on November 26th killed West Virginia National Guard Spc. Sarah Beckstrom and wounded Staff Sgt. Andrew Wolfe, Afghans as a whole have come under new scrutiny in the U.S. While the administration discusses revetting all Afghan allies, the Special Immigrant Visa (SIV) program has been paused and the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program (USRAP) remains effectively suspended for Afghan applicants.

Amidst the shifting national conversation about our allies’ service, SOF veterans shared their concerns with the Special Operations Association of America about the impact these changes have on the Afghans who stood shoulder-to-shoulder with them in combat.

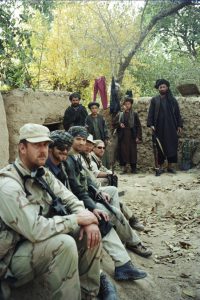

ODA 595 Capt. Mark Nutsch plans for engagement with Team Alpha and Abdul Rashid Dostum. Courtesy of Justin Sapp.

ODA 595 Capt. Mark Nutsch plans for engagement with Team Alpha and Abdul Rashid Dostum. Courtesy of Justin Sapp.

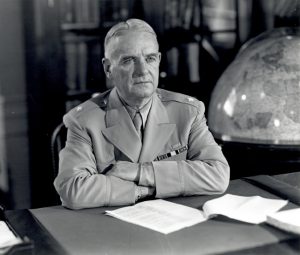

Retired Special Forces Col. Justin Sapp

29-year-old Green Beret Capt. Justin Sapp was detailed to the CIA when he was dropped by helicopter into Afghanistan in mid-October 2001. Part of an eight-man team of elite U.S. military and paramilitary personnel dubbed Team Alpha, Sapp’s mission was to link up with Special Forces ODA 595 and work with Afghan ground forces from the Northern Alliance to beat back the Taliban in northern Afghanistan.

Sapp entered Afghanistan with just two bags containing primarily weapons and radios. As Team Alpha worked their way to Mazar-e Sharif to liberate the city, Sapp said “we were dependent on [our Afghan counterparts] for security, for food, for lodging, for everything.”

“We were eight people on the ground,” Sapp explained. “Afghans were the main effort…without that support, we would not have been successful.”

Their mission would be a success, as detailed in Toby Harnden’s book First Casualty, which tells Team Alpha’s story. The operation came at a stark cost when Team Alpha member Mike Spann, a CIA paramilitary officer, became the first U.S. casualty in Afghanistan on Nov. 25, 2001.

Spann’s memory lives on today through the nonprofit organization that his widow and Team Alpha members have created to support the roughly 300 Afghan families who enabled their success. The nonprofit helps the Afghan families pursue entry, and safety, in the U.S. via USRAP. The group’s name, Badger Six, is a tribute to the call sign Sapp and Spann used for one another in Afghanistan.

During the four years following the withdrawal from Afghanistan, Badger Six was able to get roughly half of the Afghans who enabled their efforts to safety in the U.S. “They’ve all been very successful,” Sapp reported.

When the USRAP was suspended on January 20th, Team Alpha enablers living in third countries and in a Qatar processing facility faced an uncertain future. As Afghans fell under greater scrutiny in recent weeks, the situation has only grown more dire.

Amidst conversations about new vetting measures and increasingly strict travel bans, Sapp advocated for discernment for populations that “were instrumental to the success of the United States.”

Sapp also warned of the difficulties the U.S. may have in the future when trying to gain support from local populations, a theme SOAA examined in a recent article.

“When people see that the United States cannot make a distinction between the good guys and the bad guys and support them in a very discerning manner, you’re going to hurt our brand in the world,” Sapp said.

Sapp isn’t the only one voicing concerns.

Retired Green Beret Vince Leyva

After Vince Leyva retired from a 24-year military career that included 18 years in the Special Forces, he took on contracting work in Afghanistan. First, Leyva advised Green Berets about the evolving Taliban improvised explosive device (IED) threat. In 2015, he began to train members of an elite national Afghan counter-IED unit, the National Mine Reduction Group (NMRG).

Leyva says the NMRG were “always out front,” tasked with alleviating “any threat or mitigat[ing] any dangers so that our Green Berets didn’t have a problem” with IEDs.

The NMRG were particularly skilled at visually finding Iranian-sourced low-metal-content IEDs that standard metal detectors rarely picked up. Because of the NMRG’s unsurpassed detection skills, Leyva said he always urged Afghan commandos working alongside Green Berets not to leave the wire at night without personnel from the NMRG attached.

On one devastating occasion in Kunduz province, Leyva told of an instance when the commandos failed to heed his warning. That night, Leyva and others awoke to the sound of three explosions in a row as the commandos triggered a series of hidden IEDs.

What came next was a “mass casualty exercise,” Leyva explained. “We had double amputees, we had guys without arms.” Though the commandos survived, Leyva explained that the incident “was just catastrophic,” especially because medical support for amputees in Afghanistan is crude at best.

Then, in 2016, an NMRG member came to Leyva asking for a letter of recommendation for the SIV program. Over the passing years, Leyva wrote countless letters in support of NMRG members he personally trained and operated alongside. While some have obtained visas and transitioned into successful careers in the U.S. as truckers and security guards, others have been unsuccessful in achieving an SIV and remain in their homeland under threat.

Though some onlookers have concerns about how the U.S. government is vetting allies for U.S. programs, Leyva said that vetting has always been “very strict,” despite NMRG personnel having been put through security checks every six months due to the nature of their work. Leyva reported that whenever those semi-annual checks turned up a problem, the individual “would be thrown immediately off the program, and they would not be eligible for an SIV.”

If the SIV program were to remain paused, Leyva worries that “it looks like a bad, bad stain” on the country. Particularly for the sake of Green Berets who will need to find host nation partners in the future, Leyva urged U.S. leaders to go “back to [the SIV] process and at least get these individuals that actually worked for us out of that country and into America so they can start a new life.”

Within the world of SOF veterans, Green Berets are not the only ones advocating for their Afghanistan partners.

Cultural Support Team member Rebekah Edmondson

Army veteran Rebekah Edmondson served as a Cultural Support Team (CST) member between 2012 and 2016, participating in direct-action missions and night raids alongside SOF personnel to grant them access to the Afghan women and children living alongside high-value targets.

In her CST role, Rebekah helped train her Afghan counterparts in the female tactical platoon (FTP). “It was probably the greatest accomplishment of my life,” Edmondson said of the effort, describing the “feeling of shared success” as the CST and FTP members proved themselves to the men who traditionally occupy the special operations environment.

It was also Edmondson’s job “to go out and try to find Afghan women that were bold and…crazy enough to do the job that we were asking them to do.” Not only did the women have to be vetted and screened prior to employment, but they also had to get a signature from their father or another male relative to allow them to participate in the FTP.

“There’s absolutely no way that we could have gotten buy-in from individuals like that if they knew that the American government would not protect them in case of emergency,” Edmondson said.

Unfortunately, by the time emergency was imminent, there was no pathway in place to support FTP members. American leaders believed that the Afghan government would hold out against the Taliban, but Rebekah said that many of the FTP members “already saw the writing on the wall” of the impending takeover.

Edmondson worked with other veterans to help about 50 FTP members navigate to Hamid Karzai International Airport to be evacuated during the withdrawal. Afterwards, she worked with a variety of non-governmental organizations, colleges, and refugee resettlement groups to advocate for FTP members arriving in the U.S.

Upon arrival after the withdrawal, FTP members received two years of humanitarian parole. They had no durable pathway to security in the U.S. because service with the Afghan government does not qualify Afghans for the SIV program. The FTP members “arrived and they had to apply for asylum even though they were brought over here all through the proper channels [and] manifested on military aircraft,” Edmondson said. “To have to turn around and try to justify why they should be able to remain here, I personally see that as a slap in the face,” she explained. “They just remain in utter limbo.” Without an accurate timeline, these brave American allies cannot move on with their lives.

In addition to forging a pathway through uncertainty, many FTP members struggle through ongoing separation from the families they were forced to leave in Afghanistan.

Edmondson also supports FTP members who were left behind in their homeland. Because of the Taliban’s policies restricting women’s rights, these women are not able to work, to go out in public, or to seek an education. They also must live in hiding due to the nature of their employment. With the suspension of the USRAP, there appears to be no path forward for our FTP allies.

Edmondson has started her own nonprofit, NXT Mission, which exclusively serves the multifaceted needs of the FTP population. But recent policy announcements threaten to upend or destabilize those efforts.

Edmondson said that she is “begging for mercy” for the FTP members in need of support. “They deserve justice. They deserve safety. They deserve peace…For veterans like myself and other people that have worked with these individuals, we cannot move on with our lives until they can.”

Changing the Conversation

The active duty and veteran SOF personnel who make up the SOAA team keenly understand that having the trust of local allies is a key enabler for the success of special operations teams working at the tip of the spear. We stand with SOF veterans as they work to preserve U.S. government promises and protect the Afghans whose sacrifices saved American lives.

We urge American leaders to resume vetting and processing our trusted allies through the SIV program and USRAP. Not only will this reduce a moral burden on SOF elements who have devoted years to keeping their counterparts alive, but it will repair America’s reputation, ensuring that future SOF personnel can more easily win popular support on the battlefield.

When SOF personnel show up in a foreign land, they must be able to work by, with, and through the local population. One way to all but guarantee that partnership happens is to take care of the local allies once SOF has departed the region. This is how we keep America safe.

The men and women of the Special Operations community know that success on the battlefield has never come from technology or firepower alone, rather, it comes from trust. Our Afghan partners earned that trust in the harshest places imaginable. They protected our SOF soldiers, shared our risks, and carried our fight as their own. Many paid for it with everything they had. Now, with the future uncertain and the programs meant to safeguard them suspended, we are the ones being tested.

Restoring the SIV and USRAP programs isn’t just about visas or paperwork. It’s about finishing what we started. Each week of delay leaves families in hiding, veterans haunted by unanswered pleas, and a country’s moral credibility a little more fragile. Restarting these pathways would ease a burden that never should have fallen so heavily on volunteer networks of veterans and nonprofits. More importantly, it would tell the world that America stands by those who stood by us, even when it’s no longer convenient.

When U.S. SOF deploy again, and they will, they will have to work with local partners who watch how we treat today’s allies. Those relationships can’t be bought; they’re built on faith and reputation. Abandoning those who fought beside us stains both. Taking care of our Afghan partners is not just an act of gratitude, it’s a matter of future readiness, national honor, and strategic importance. If we fail them now, we’ll spend decades trying to rebuild the kind of trust they once gave us freely. And we’ll make it harder for SOF personnel the next time they have to work with a partner force in furtherance of U.S. national objectives.

ODA 595 Capt. Mark Nutsch plans for engagement with Team Alpha and Abdul Rashid Dostum. Courtesy of Justin Sapp.

ODA 595 Capt. Mark Nutsch plans for engagement with Team Alpha and Abdul Rashid Dostum. Courtesy of Justin Sapp.